Can agricultural advisory services provide business opportunities for agro-input dealers?

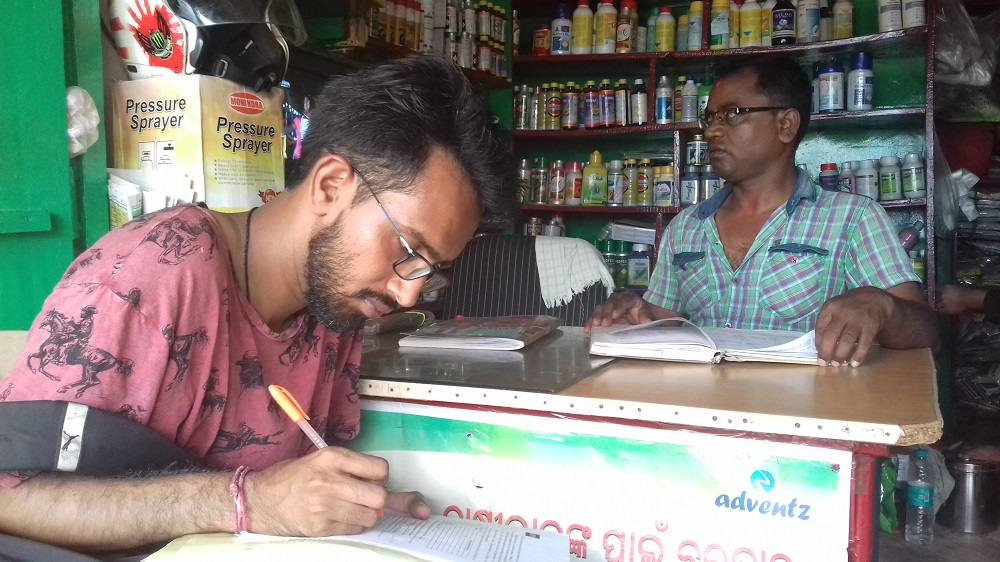

Interviewing an input dealer as a potential conduit for the dissemination of RCM recommendations. (Photo by Manas Ranjan Sahoo)

In Odisha, India, the agricultural sector has a domineering influence on the life and livelihood of 61% of the populace and, thus, holds the key to the socioeconomic development of the state. Because rice is the state’s principal crop, its low productivity, which is below the national average, has been affecting the sector significantly for some time.

One of the major reasons widely cited for the low yield and income of the farmers in the state is poor nutrient management in terms of quantity and the timing of application. One significant way of overcoming this problem is through customized agricultural advisory services on nutrient management.

Routing fertilizer information

Under this objective, the government of Odisha has been promoting Rice Crop Manager (RCM), a web-based software developed by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), as part of the emerging role of information and communication technology (ICT) in the agribusiness sector. To disseminate the recommendations, IRRI uses its staff, community resource persons, and public dissemination channels such as village agricultural workers. (See An app tailor-made for India’s rice farmers.)

RCM centers (or kendras) are also an important path for delivering the recommendations. The RCM kendras are equipped with ICT devices used by trained agricultural extension staff. The centers were established under a project implemented by IRRI and the government of Odisha to increase the productivity of rice-based cropping systems and farmers’ income in the state.

Some nongovernment RCM kendras also complement the government-run centers.

Efforts are being made to popularize RCM kendras among farming communities and to encourage farmers to visit them before the start of each cropping season to receive personalized recommendations for their rice crop.

In addition to the kendras, RCM opens up potential avenues to improve the scalability and accessibility of agricultural advisory services through private extension agents. In India, input dealers are rated as the most significant source of information for farmers, making them a significant category of private extension agents.

Our study was an exploratory attempt to determine the possibilities of making input dealers a major dissemination channel for RCM interventions as well as to ascertain farmers’ willingness to pay for private extension services.

Understanding the players

We conducted our study in Puri District because, in addition to being agriculturally rich, the district serves as the hub of IRRI and RCM activities.

A total of 50 farmers were randomly chosen from the farmer population provided with RCM recommendations during the 2016-17 rabi season. Our sample group consisted primarily of small and marginal farmers with an average landholding size of 1.3 hectares. Half of the farmers were monitored by IRRI staff, village agricultural workers, or nongovernment organizations throughout the season to ensure that they followed the RCM recommendations provided. The other half was not monitored. The management practices for both plots were similar in all aspects except nutrient application.

Among the factors we explored were the differences in the cost of cultivation and yield between RCM practices and farmers’ own practices, and the farmers’ satisfaction with the RCM recommendations. We also examined their willingness to receive RCM recommendations for the coming seasons and to pay for the service from fertilizer input dealers as well as their diversity in terms of willingness to pay.

Thirty-four dealers were randomly chosen and surveyed to identify the variation in their socioeconomic characteristics, business operations, and, more importantly, their responses toward advocating RCM interventions as a potential business model. The dealers in our sample had a fair amount of experience as input dealers, with an average of 16 years. Most of the dealers had small firms, with a few wholesalers included. They indicated that the major share of their income came from fertilizer business.

Interviewing a farmer on his willingness to pay for RCM recommendation from input dealers. (Photo by Manas Ranjan Sahoo)

Revealing numbers and behaviors

We asked the farmers to mark their preferences for the existing dissemination channels as well as the proposed private (paid) input dealer channels. A big revelation in the study was that, in the absence of “doorstep delivery” of RCM recommendations, farmers were inclined to obtain the services from nearby input dealers at a minimal cost—with a few even ready to shell out an average amount of USD 0.77—rather than availing of the free services from RCM kendras located about 15 kilometers (on average) from their homes. We also found that the more educated and the younger farmers were more receptive to RCM technology as they were ready to purchase the recommendations from dealers even at higher costs.

In a season, farmers visit the RCM kendras located in block or district offices less frequently than agricultural supply dealers. The study revealed that 72% of the sample farmers reported at least quarterly visits to dealer shops in a year but only 12% visited the kendras at least once. Also, 84% of the sample farmers had been purchasing from the same input dealer for more than 10 years.

The preference of the farmers to pay for agricultural advisory services from private extension dealers over the free services offered by RCM kendras reveals that (a) farmers, because of more frequent contact and better accessibility, have developed a better rapport with input dealers than with public extension systems located far away, and (b) even small and marginal farmers see considerable promise in RCM technology for gaining agricultural prosperity.

Our study also revealed that the farmers’ way of using fertilizer followed a highly skewed consumption pattern in which their average application of MOP and DAP was above the average level recommended by RCM. At the same time, the amount of urea they used was below that of the average RCM recommendation.

The role of balanced fertilizer application in bringing in considerable change need not be overemphasized. The farmers in the RCM plots reported an average yield gain of 2 tons/hectare vis-à-vis the plots under the farmers’ own practice. In these smallholder plots, the yield gain through balanced nutrient management can bring in additional returns of more than USD 77/hectare and can lead to potential agricultural progress.

In addition, 96% of our sample farmers perceived production and productivity gains while 92% realized a potential cultivation cost reduction from the adoption of RCM technology.

Information dealers

An equally important step, apart from obtaining farmers’ perceptions, toward establishing ICT-based agricultural advisory services on a business scale would be obtaining the perceptions and responses of input dealers toward the sale of RCM recommendations from their shops. All the dealers in our sample responded positively to adopting RCM interventions on a business scale at minimal service costs.

Among the dealers, 85% told us that they had given suggestions to farmers on fertilizer doses and, hence, the amount of fertilizer they needed to purchase. A good 76% of the dealers reported that farmers actually paid attention to their suggestions. This is particularly important considering that an average of 800 farmers visit each dealer’s establishment annually. Out of these, approximately 300 farmers were their long-time customers who visit them 18 times a year on an average. The distribution of RCM recommendations through input dealers would give their suggestions a scientific basis. This would also give RCM technology wider coverage and help ensure higher compliance of farmers with the recommendations.

Setting up an ICT establishment and proficiency in operating an ICT device are the two essential requirements needed for instituting the dissemination of RCM interventions in a commercial mode. We also looked at the ICT-readiness of the dealers in terms of personnel and facilities. Every shop had an average of two employees, with at least one being proficient in using ICT tools.

Although only 15% of the dealer respondents presently have the required ICT facilities at their stores to generate and sell RCM recommendations, all of them were willing to make the sale of RCM recommendations a supportive side business and put up the required infrastructure.

When asked about the potential benefits they perceived from the sale of RCM recommendations as a side business, the majority opined that this would serve as a new source of income and a form of service to the farming community.

A new information delivery ecosystem

This study should be seen as a pilot attempt to examine the possibility of setting up a proposed ICT intervention business model.

The readiness shown by farmers and dealers toward this potential business proposal has given us confidence about opening up new avenues for better and wider dissemination of RCM technology. The efforts required in training input dealers or their staff in operating the RCM app would also be minimal since they are already acquainted with ICT devices and are knowledgeable about agricultural practices.

Although the results are positive, our study further warrants a detailed and elaborate business diagnostic study to represent the entire state and pilot-test the model.

_____________________

Drs. Varkey, Patil, and Veettil are an assistant scientist, associate scientist, and scientist, respectively, in the Agri-Food Policy Platform at IRRI India. Ms. Bharti and Dr. Sharma are specialist and scientist, respectively, in the Sustainable Impact Platform at IRRI India. Mr. Yadav is a student at Assam Agricultural University and an intern at IRRI India.