CGIAR centers are collaborating with the Department of Farmers’ Empowerment of Odisha to bring rice fallows into cultivation under the Comprehensive Rice Fallow Management Project. The project aims to make the fallow lands during the rabi season productive and increase pulses and oilseed crop production. The success of fallow cropping, initially using low-input crops like green gram and black gram, is the best way to motivate farmers to explore more remunerative crops in rice fallows with supplemental irrigation.

Growing pulses and oilseeds crops in rice fallows provide farmers with additional income, livelihood opportunities, and food and nutrition security. (Photo: IRRI India)

/

In the past two decades, Odisha has demonstrated remarkable resilience to droughts, cyclones, and floods. The state has achieved surplus paddy production thanks to timely and effective government actions such as improving irrigation facilities and promoting stress-tolerant crop varieties and climate-smart crop establishment methods like direct-seeded rice (DSR).

Odisha has 6.15 million hectares (ha) of agricultural land and over half is under paddy cultivation. However, following the kharif rice crop, a significant portion of land remains fallow during the rabi season.

Farmers in the coastal districts of Puri, Jagatsinghpur, and Jajpur and the irrigated belts in Sambalpur, Bargarh, and parts of Koraput and Kalahandi can grow green gram, black gram, chickpea, lentils, mustard, sunflower, sesame, and others crops during the rabi season.

But this is not the case in the uplands and medium lands in western and southern Odisha where farmers cannot grow a second crop because the soil is too dry. The opposite is true in the state’s lowlands coastal areas where the soil is too wet after the rice harvest preventing farmers from growing rabi crops.

Other factors compel farmers to plant only rice crops. Cultivating long-duration rice varieties that take around five months before they can be harvested gives them little time to plant another crop.

The shortage of agricultural workers is another issue because traditional planting methods are labor-intensive. Insufficient irrigation, open livestock grazing after rice harvest, and fragmented land holdings limit farmers’ opportunities to grow a second crop.

Optimizing agricultural land use, diversifying income sources and diet

Pulses and oilseed crops complement the food basket with much-needed proteins and essential fats for ensuring nutritional security. Legumes are inexpensive dietary protein and supplement the lysine absent in cereals. This helps address Protein Energy Malnutrition prevalent in cereal-based vegetarian diets.

Pulses and oil-rich legumes like groundnuts can also restore and improve soil fertility through nitrogen fixation. Oilseed crops, when grown in rotation with pulses, reduce the depletion of soil organic matter that occurs with the continuous cropping of pulses.

These crops also ensure year-round cultivation and production enabling farmers to increase their income and profits and provide additional livelihood.

Despite these benefits, Odisha continues to face pulse and oilseeds production deficits.

Comprehensive intervention for a traditional practice

The Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Empowerment (DA&FE) initiated the Comprehensive Rice Fallow Management (CRFM) Program to make the fallow lands during the rabi season productive and increase pulses and oilseed crop production.

The program is implemented by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), and the World Vegetable Centre (WorldVeg), the Agricultural Finance Corporation Ltd., and Krishi Vikas Sahakari Samiti Limited.

In 2022-23, CRFM was successfully implemented across 30 districts covering approximately 70,000 ha. The program plans to expand the cultivation of pulses and oilseeds to 400,000 ha of fallowed land in 2023-24.

A technology-based approach to rice fallow intensification

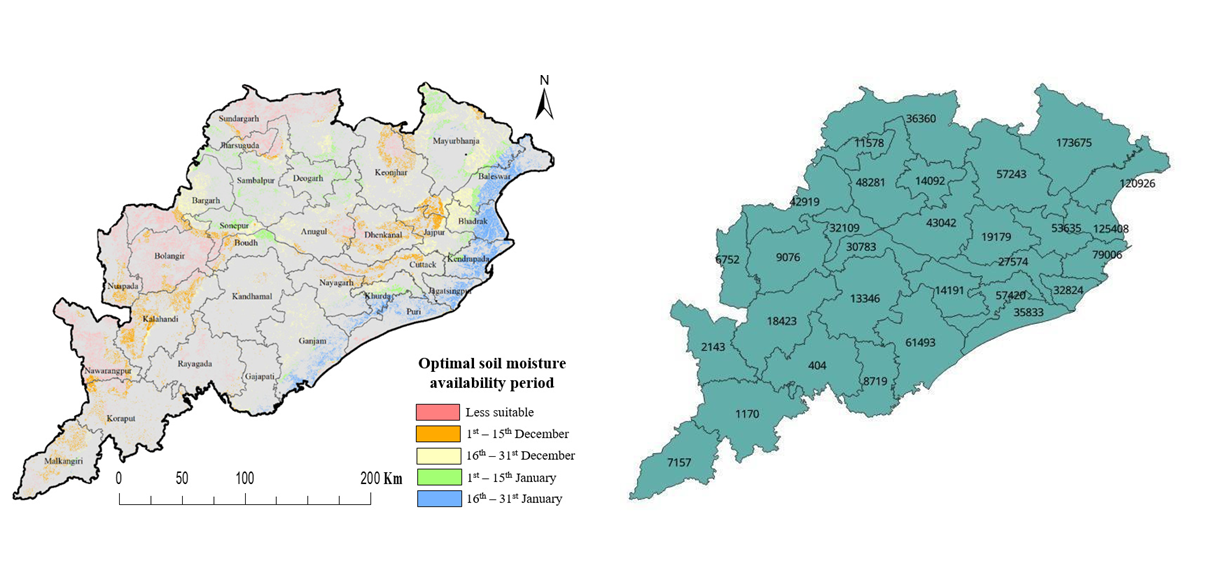

IRRI mapped and assessed rice fallow areas in Odisha for suitability based on soil moisture using satellite imagery from Sentinel-1 and Landsat 8. From 2015 to 2021, IRRI identified an estimated area of 2 million ha of rice fallows, more than half of which were found suitable for cultivating water-efficient rabi crops like pulses and oilseeds. (See Fig. 1)

Fig 1. Spatial distribution of optimal soil moisture availability period and area for targeting rabi crops in rice fallow areas in Odisha.

.

To turn the underutilized lands into productive areas, IRRI has introduced viable options such as shorter-duration rice varieties and sequence crops that can be harvested about one month earlier than long-duration crop varieties.

Among the rice varieties for the kharif season the institute introduced, tested, and promoted in uplands and medium lands are Sahabhagi dhan, BINA dhan-11, MTU-1156, DRR-42, and DRR-44). For the rabi season, IRRI recommended Virat and Shikha (green gram); VBN-8, PU-31, PU-35 (black gram), Giriraj (mustard); Amrit and Suprava (sesame), and rapeseed.

An important part of encouraging farmers to fallow cultivation is giving them access to the promoted varieties. The Odisha State Seed Corporation received breeder and foundation seeds to bring improved, high-yielding varieties closer to the farmers.

Sustainable rice fallow cropping

Although fallows are deemed as unproductive, the practice has ecological, economic, and social importance to rural people, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). However, the increasing population and the need to produce more food resulted in reduced fallow periods

Fallows allow the soil to restore its fertility. Because many smallholder farmers depend on fallowing, rather than expensive fertilizers, to improve nutrient-depleted soils, the FAO suggests that farm productivity and income could decline steadily over the years.

Several promising technologies have been developed to improve yields and restore soil fertility that will ensure the sustainability of rice fallow cultivation

These include climate-smart practices such as growing two crops in the same field, one after the other in the same year (sequential cropping), cultivating nitrogen-fixing legumes, using dolomite for acid soil management, and multi-crop seed drills.

CRFM also promotes environment-friendly integrated pest management, including biocontrol of plant diseases using rhizobial inoculants, phosphate solubilizing microorganisms, Trichoderma, and other non-chemical pest control measures such as solar and sticky traps.

The farmers received training on proper land preparation, seed treatment, integrated nutrient and weed management, and simple but effective technologies such as IRRI super bags for storing pulses to avoid post-harvest losses.

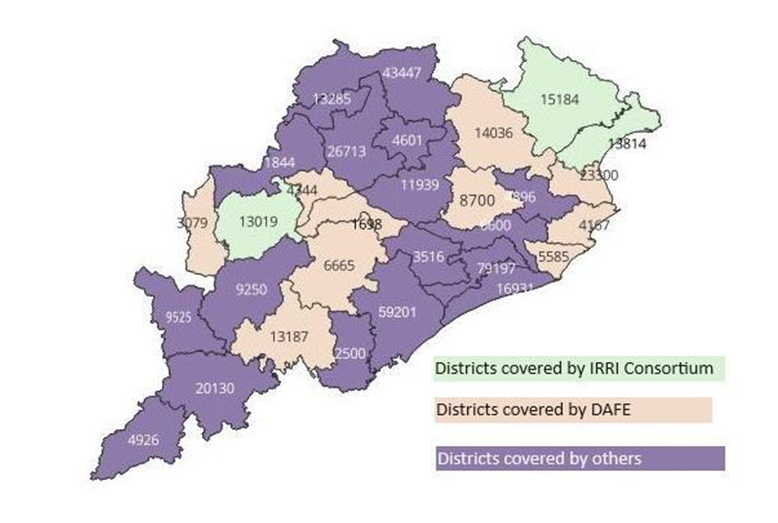

Fig 2. Based on the extrapolation domain maps of rice fallows, CRFM planned to cover 314 blocks in 30 districts (400,000 ha) during 2023-2024 rabi season. The DA&FE will cover 82 blocks in 10 districts (115,200 ha) while other implementing agencies will cover 232 blocks in 20 districts (282,200 ha). IRRI, ICARDA, and WorldVeg are implementing CRFM on 95,650 ha of fallows in 3,491 clusters in 52 blocks in Balangir, Baleshwar, and Mayurbhanj Districts.

.

A cluster approach to fallow intensification

Non-government organizations, in consultation with the block-level officials of the DA&FE, selected different farmers that owned contiguous patches of land to form clusters.

In each cluster, 11% were led by women, a farmer collaborator was appointed as leader or facilitator responsible for receiving and distributing seed and other inputs to the other farmers.

They also help organize meetings and liaise with the 52 block coordinators to relay information on farmer credentials, the progress of activities, and the concerns of the farmers.

In consultation with the district coordinators engaged by the CGIAR Centers, block coordinators upload the information to the Analytics for Decision-making and Agriculture Policy Transformation Portal of Odisha.

The cluster approach proved effective and efficient in facilitating the coordination efforts of the government and implementing agencies for input and extension service provision and capacity building.

Interestingly, this approach had some unintended benefits. Although implementing agencies addressed most of the technical constraints for fallow cropping, the major issue voiced by the farmers was the open livestock grazing after the rice harvest.

Through the clusters, farmers devised ways to protect their crops. Some clusters installed nets while others used solar-powered electric fence. The farmers found them immensely helpful because they eliminated the need to guard their crops, especially at night, from grazing cattle.

Attaining the critical mass to spur widespread adoption

Through the efforts of other government-supported programs like the Targeting rice fallow areas in eastern India, pulses and oilseed crops are now being cultivated in 50,000 ha and 4,000 ha, respectively. However, the impact has been inadequate and did not stimulate widespread adoption.

CRFM mobilizes thousands of farmers through farmer groups, research and development institutions, and government, and non-government organizations within a period of one crop season is a massive, first-of-its-kind initiative that has high potential to reach critical mass for sustained adoption of double cropping in rice fallows.

Attaining critical mass is important for the exponential increase in adopting new technology. A minimum number of adopters is required for an innovation to become self-sustaining. Critical mass also creates a feedback loop which, when primarily positive, accelerates the adoption of innovations.

As more people adopt the innovation, it becomes more visible and gains social acceptance. This, in turn, encourages more people to try it, leading to a snowball effect.

Women farmers from the Jagannath Producer Group cultivating grass pea in Odiapali, Balangir. Engaging women in fallow cultivation helps accelerate crop diversification, increase women’s incomes, and reduce the gender gap in agriculture. (Photo: IRRI India)

.

A holistic model for rice fallow systems

Farmers are central to the transition towards sustainable food production during fallow periods. However, numerous challenges stand in their way that prevent the wide-scale adoption of technology.

IRRI is laying down a holistic strategy to encourage farmers to try sustainable rice fallow cropping. The institute will engage more women through self-help groups and farmer producer organizations to lead more farmer clusters. This will help accelerate diversification, increase women’s incomes, and reduce the gender gap in agriculture.

Integrating social and behavioral change communication in encouraging fallow cropping will also help the move towards cultivating nutritious crops and dietary diversity as well as the environmental and livelihood benefits that come with it.

Developing a self-sustaining seed system to make seeds available locally in time for farmers to sow rabi crops before soil moisture gets depleted, particularly in the rainfed areas of western and southern Odisha, is an important part of the equation.

This model has a high potential for replication in Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and other states with substantial fallow areas.

The success of fallow cropping, initially using low-input crops like green gram and black gram, is the best way to motivate farmers to explore more remunerative crops in rice fallows with supplemental irrigation.

The Comprehensive Rice Fallow Management Project is funded by the Odisha State Government.