Dr. Robert Chandler was appointed by the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations to be IRRI’s first director general and charged with a mission to develop higher-yielding rice varieties in the face of famine in Asia. In the final analysis, he was certainly the right person at the right place and right time to get the ball rolling for rice research in the early 1960s.

One of his outstanding leadership qualities was his attention to careful staffing. The way he assembled an international team of rice researchers, including Peter Jennings, Hank Beachell, Akira Tanaka, T.T. Chang, S.K. De Datta, and many others, was brilliant. Chandler found persons who had the background and who wanted to do the job. He then gave them an environment in which they could excel. The persons had to be well qualified in the basics of their fields but prior knowledge of rice was far less important under Chandler’s management than a desire to take the ball and run with it.

Of Chandler, Peter Jennings (see below) said that “he was well named: Robert ‘Flint’ Chandler. He was ‘flinty’, a stereotypical New England Yankee, very direct, hyper-enthusiastic. He maintained a profound barrier between himself and his staff; he was nobody’s pal. But with all of that, he was, by far, the best director of an institution I’ve seen in 50 years.”

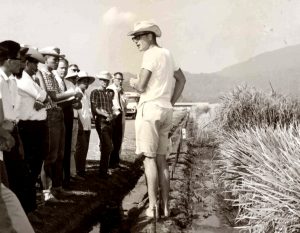

Dr. Peter Jennings (photo, left) was IRRI’s first breeder charged with heading the then Varietal Improvement Department in 1961. Prior to this, in 1957, the Rockefeller Foundation had sent Jennings, a young plant pathologist with a PhD from Purdue University, to Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana to learn about rice initially to develop new rice varieties for Latin America. During his time in Texas, he spent a training period with Henry “Hank” M. Beachell, the rice breeder at the rice research station in Beaumont. Jennings would later recommend that Beachell, whom he called the best rice breeder in the world at the time, be brought to IRRI as a consultant for one month (see more about Beachell below) and ultimately come to IRRI as a second rice breeder on the staff.

The Rockefeller Foundation then sent Jennings to Mexico and Colombia. In Colombia, he developed an excellent rice research and training program. After a trip through Asia in the autumn of 1960, Jennings developed a keen interest in the rice problems of the Asian tropics, so it was only logical that he move on to IRRI to help it develop its fledgling rice research program. He was perhaps the linchpin in the development of IR8.

During that 1960 trip, Jennings and Sterling Wortman, a plant geneticist for Rockefeller Foundation (see below), who later became IRRI’s associate director, traveled across Asia in 1960, looking at rice varieties, meeting rice scientists, and interviewing prospective trainees and staff for the new IRRI. In India, they saw Taichung Native 1 (TN1), a Taiwanese variety that was actually the first semidwarf variety in the tropics, grown mostly in Taiwan. Having Dee-geo-woo-gen (DGWG) as the dwarf parent (as did the future IR8), TN1 yielded much better than tall varieties, but was highly susceptible to major disease and insect pests. So, there was still a great need to develop a much better semidwarf variety.

Jennings and Akiro Tanaka, IRRI’s first plant physiologist (see below), conceptualized the traits of a semidwarf rice plant and systematically studied the causes, and effects, of lodging during IRRI’s first 3 years. By then, the 38 crosses made using the materials, which might emulate the required traits, including the Peta x DGWG cross, had been made. Ultimately, Jennings discarded the tall, late-maturing plants from the Peta-DGWG cross and others and saved only short, early-maturing plants. (See more details about this in the introduction, IR8, a rice variety for the ages.)

Also, Jennings eloquently tells the full story in an IRRI Pioneer Interview done in July 2007. In 1967, after his work in Asia was completed, Jennings returned to Colombia where he had a long career in Latin America. See his piece on the Rice revolutions in Latin America.

Henry “Hank” M. Beachell (photos in 1967 with Chandler and the John D. Rockefeller III and in 2006 on his 100th birthday with Nobel Laureate Norman Borlaug) arrived in 1963 at IRRI from the Beaumont Experiment Station in Texas as IRRI’s second full-time rice breeder. Jennings, who was about to depart on a sabbatical leave, wanted to have a breeder of the stature of Beachell to pick up where he left off. And that he did.

From the third (F3) generation, Beachell selected 298 of the best individual plants. Seeds from each plant were sown as individual “pedigree rows”—the fourth (F4) generation. He selected from row 288, a single plant—the third one—and he designated it to be IR8-288-3. Its seeds, the fifth generation (F5), were grown to produce the basic IR8-288-3 seed stock. IR8-288-3 was eventually named as variety IR8.

The seed of IR8 was uniform enough for trials in other countries, but a couple of years later, Beachell devoted considerable effort to producing an extremely pure strain that would serve as a uniform seed source of IR8 for the future. Meanwhile, IRRI sent seeds of IR8 and other promising lines to national rice programs across Asia for testing.

In a 1994 video, Beachell confessed tongue-in-cheek that he was foolish enough to actually eat IR8, but that he wanted to eat it right out of the pot. “I didn’t want it to set around very long because it would get hard and would indeed scratch the throat,” he said. “But cooking and milling quality were secondary; the main thing was production at the time.”

For his body of work in Texas, IRRI headquarters, and IRRI outreach in Indonesia, he was named a co-winner of the 1996 World Food Prize Laureate. He passed away at his home in Texas just 83 days after celebrating his 100th birthday on 21 September 2006.

Mr. Rodolfo ‘Rudy’ Aquino, a 25-year-old research assistant at the time on IRRI’s national staff, worked with Peter Jennings in 1962 to come up with a list of 38 crosses including both short- and tall-statured materials from Taiwan, Indonesia, and elsewhere.

Among his unsung tasks was indeed a historic one in that he was the technician who actually did the pollinating for many of the crosses involving the material mentioned, one of which (Dee-geo-woo-gen x Peta) ultimately led to IR8. He served IRRI for 35 years (1962-97) working his way up to senior associate scientist on the national staff before retiring in 1997. During that time, he was involved in practically every step or phase of breeding rice, singly or jointly with his fellow researchers.

In 1995, he was deservedly named one of 20 great Asians by Asiaweek Magazine. Aquino, who lives in Binan, Philippines with his wife, Rosalie, wrote recently, “I am grateful for the opportunity to have worked with IRRI. It helped me fulfill my dream to be a rice researcher and worker.” Read more about what he wrote about on his time at IRRI.

Dr. Akira Tanaka, IRRI’s first physiologist, arrived at the institute in April 1962 to head the fledgling institution’s Physiology Department. Japanese researchers, such as Tanaka, played a key role at IRRI as it set the stage for the start of the Green Revolution.

According to Peter Jennings, he was, by far, the most experienced rice scientist at IRRI in those days. The photo shows Tanaka (left), conferring with Jennings during the early 1960s.

“Tanaka’s love was mineral nutrition, particularly, deficiencies, but his job at IRRI was really to take the tropical rice plant apart, analyze it—the stems, the leaves, the architecture, said Jennings. “He had all this experience and his contribution to the development of IR8 was equivalent to that of a breeder. “He helped to define the course, the way. Without Tanaka, I think, IRRI would have struggled longer in developing the first semidwarf rice variety. He lives in my mind as a superb scientist who had an immeasurable impact on the development of semidwarf rice varieties that revolutionized the world’s rice production.”

Tanaka, who returned to Japan in 1966 to continue his research career, passed away there on 28 August 2016.

Other contributors

Dr. Sterling Wortman, a plant geneticist, who was a key leader in the Green Revolution, worked most of his career for the Rockefeller Foundation, which sought to fight famine in poor regions of the world by developing high-yielding ”miracle grains.” As already mentioned, in the early days, before becoming assistant, and then associate, director of IRRI (1960-64), he travelled with Peter Jennings around Asia to find rice varieties for crossing and possible new staff for IRRI to set the stage for the breeding program to get on track. Robert Chandler said, “Wortman’s contribution to the progress of IRRI in those early years cannot be overestimated.” Unfortunately, he passed away in 1981 at the young age of 58.

During the 1966 dry season, Dr. S.K. De Datta, a young Indian agronomist who had joined IRRI in early 1964, demonstrated IR8’s yield potential. He examined the variety’s fertilizer response, along with other varieties. “We wanted to determine maximum yields under the best management possible,” he said.

De Datta was amazed when he harvested the trials in May. IR8 averaged 9.4 tons per hectare, yielding as high as 10.3 tons per hectare in one trial. Average yields in the Philippines then were about 1 ton per hectare. “The IR8 yield data were the most exciting thing that ever happened to me,” recalled De Datta who spent 28 years at IRRI an IRRI agronomist and principal scientist (1964-92).

Not much was known about the genetics of tropical rice varieties in the early 1960s, so Robert Chandler, in 1961, hired IRRI’s first geneticist, Te Tzu ‘T.T.’ Chang, from Taiwan, as part of the institute’s original group of scientists. Chang began studying the inheritance of plant height. He also assisted Jennings in quickly assembling a large collection of rice varieties, including the short-statured varieties from his native Taiwan.

Chang and Jennings co-signed a letter that was sent to rice workers and experiment stations in around 60 countries requesting any germplasm (in small seed samples) they would be willing to share with IRRI. According to Jennings, the response was wonderful. “Within months, boxes and boxes of seed packages came in,” he said. “And within 2 or 3 years, we had several thousand accessions.”

From that early assemblage of germplasm, Jennings and his team made the crosses that ultimately resulted in IR8. Chang who spent 30 years at IRRI collecting and storing rice varieties from all over Asia and the world, founded the International Rice Germplasm Center, one of the predecessors of institute’s Genetic Resources Center. He passed away, at age 78, in 2006.