Rice breeders who target rain-fed areas struggle to emulate the success of breeders for irrigated conditions, who see their products rapidly adopted by farmers. This success stems from breeders’ clear understanding of the needs and preferences of farmers who grow irrigated rice and their ability to reproduce the irrigated production environment on the research station.

By comparison, developing improved rice varieties for non-irrigated areas has been slow and frustrating. Farmers who depend entirely on rainfall farm a bewildering array of environments, from the craggy mountains of northern Laos to the tidal flats of Bangladesh. They are often much poorer than those in irrigated areas because they produce only one rice crop per year

and eke out yields that are lower on average than those of irrigated-rice farmers. They sell less of their output, depending heavily on their rice crop for basic household food security.

Because their cash income is low, and they risk losing crops to drought and flood, farmers in rain-fed areas minimize risk by applying much less fertilizer than do irrigated-rice growers.The highly productive, fertilizer responsive varieties bred for irrigated conditions cannot tolerate the flooding and drought that commonly afflict rain-fed areas, which require varieties specifically adapted to them. Asian breeding programs have produced many such candidates, but only a few have been widely adopted by farmers — notably Mahsuri and Swarna in India and Bangladesh, and TDK 1 in Laos — and then only in relatively favorable rain-fed areas. In the driest uplands and the most flood-prone lowlands, farmers continue to grow traditional varieties.

Two reasons explain why rain-fed rice farmers are slow to adopt improved varieties. One — a problem more of extension than breeding — is that many farmers simply cannot get seed of new varieties. Another reason is that the varieties may not perform well in the challenging rain-fed environment or else lack a characteristic of unanticipated importance to farmers, such as palatability the day after cooking or ease of threshing. The complexities of developing acceptable cultivars for variable and stressful rain-fed environments require that breeders become deeply familiar with farmers’ needs and preferences.

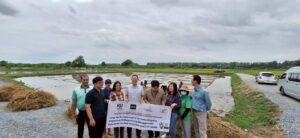

To keep improved varieties from languishing on the shelf, breeders are adopting new methods that involve farmers in varietal development at an earlier stage than traditional methods have done, testing the performance of new lines under farmer management and soliciting farmer opinion about the full range of production and enduse characteristics. These methods comprise a suite of techniques called participatory varietal selection (PVS).

Conventional rice breeding programs usually seek farmer input only at the very end of the process, when newly released varieties, usually only one or two per year, are evaluated in on-farm demonstration trials. The innovation of PVS is to involve farmers early in the selection process, to ensure that they like released varieties well enough to adopt them. What distinguishes PVS from simple on-farm testing is the emphasis on systematically collecting farmer opinions and preferences. This “innovation” is not really new. In the early 1990s, the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and its Cambodian partners annually conducted hundreds of on-farm variety trials in which farmers were asked to rate the varieties. But the incorporation over the past decade of PVS as a standard step in the breeding process has revitalized many Asian rice breeding programs.

IRRI and its collaborators have enjoyed substantial success with a set of simple techniques for institutionalizing farmer participation. At the beginning of a PVS program, focus group discussions reveal the varietal preferences and requirements of farmers, both men and women. Then farmer groups identify preferred varieties in a researcher-managed trial of a relatively large number of advanced breeding lines.