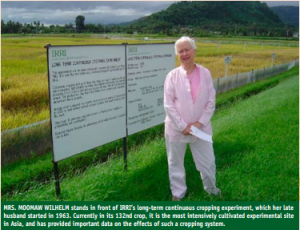

Carolyn Moomaw Wilhelm and her late husband, James (“Jim”) Curtis Moomaw, arrived at International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) headquarters in Los Baños, Philippines, in November 1961 with an infant son in tow and ready for a grand adventure. After 8 years as IRRI’s first agronomist (1961-69) and important posts in Africa and Taiwan, he passed away prematurely at age 55 in 1983. During a recent visit to IRRI—her first in 26 years—Carolyn spoke fondly about meeting and marrying Jim and their time at and beyond IRRI. Here are edited highlights of the interview.

Getting together at Washington State

Jim was the grandson of a very famous pioneer in the field of soil science, Dr. Curtis Fletcher Marbut, who did quality international work in South America, the Soviet Union, and Africa, as well as in the United States. This was always on Jim’s mind and it honed his interest in doing similar research. Jim grew up on the Branch Experiment Station in Dickinson, North Dakota, where his father, Leroy Moomaw [also an agronomist and noted for his work with crested wheat grass], was superintendent for many years. Jim had a degree in botany (ecology), with a particular interest in applied agronomy involving soils, pastures, and grasses. I met Jim at Washington State University—Washington State College in those days—in a class on soil microbiology. We were both graduate students, but he had been there several years before I met him during the 1954 fall [autumn] semester. He had come back from Alaska on crutches because he had “chopped” the wrong limb! He made an impression on me because he was on crutches—and he was my lab partner. A year passed and we didn’t pay much attention to each other. Then he visited me in the summer of 1955, when I was working at Yellowstone National Park during a break from my graduate studies. Suddenly, I realized this older man—he was 5 years older!—who had impressed me was interested in me. We were married almost immediately (within 6 months). He finished his very long research project, a study of grazing and burning of pastures in the Columbia Basin Region; I did a biochemical research project for an M.S. in the Bacteriology Department. Both of us completed our orals on 19 September 1956, packed up, and left that night en route to his first job as assistant professor of agronomy and soil science at the University of Hawaii. Hawaii in 1956 was not yet a [U.S.] state, but still a territory—and that in itself was new territory for us.

IRRI-bound on the USS Hoover

Jim was being courted by the Rockefeller Foundation, which by then [along with the Ford Foundation] had decided to establish IRRI. Originally, they were thinking Jim might go to Japan to do research in Sendai on Hokkaido. Then, Sterling Wortman [IRRI associate director, 1961-64], who had known and worked with Jim occasionally, suggested that Jim be considered for IRRI’s first agronomist position. So, Jim was invited to see IRRI as it was being built [July 1961] and to meet [Director General Robert F.] Chandler and the rest is history. We were excited, very excited. We packed up and traveled by ship on the USS Hoover from Honolulu to Yokohama [Japan] and Hong Kong prior to docking in Manila. We spent several weeks in the Manila Hotel while waiting for our house to be finished and our household effects to be cleared. That was the beginning of some very exciting times for us. Since I had already circumnavigated the globe with Jim (East Africa, Delhi, Calcutta, Bangkok, Hong Kong, and Tokyo during a Fulbright year to and from Kenya), I was not so shocked by the poverty we saw in the Philippines when we first arrived. As a child, rice certainly was not something that I ever thought of. My mother would serve it to me with cinnamon and sugar—rice pudding. Now, thanks to IRRI, we think of it in an entirely different way. I’m very snooty about rice, even today you see. I don’t want to buy that old stock that’s in the market. I know some good Asian rice stores in Dallas and New York and where I live now [in Oklahoma]. There were very few Americans at IRRI in the beginning, but there were many other nationalities and they were also excited to be a part of this new venture. However, in some respects, the women [spouses] with whom I interacted were often quite lost and lonesome without the extended families they were accustomed to. The Chinese, the Ceylonese [Sri Lankan], the Indians came from cultures in which they had strong support systems. Coming [to IRRI] was a much greater sacrifice for them than it was for me or for any of the American women [who came to IRRI with their husbands in those days].

Going to Ceylon

[In 1967] IRRI received a grant from the Ford Foundation for rice research in Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka) and Bob Chandler offered Jim the opportunity to lead the project. [At first] I didn’t want to go. We had four little boys (ages 7, 5, 2 and a half, and 1+) and I couldn’t see myself coping and I was worried about obtaining potable water, milk, good food, and other basic necessities. In the end, I agreed to go and we were quite a unit going into the IRRI program at Kandy [south-central Ceylon]. Most of the time, Jim was in the field. He was all over that island. He was so motivated to see everything and to get as many rice plots established as possible. He worked all the time and so I had my own responsibilities taking care of four sons. All of a sudden, we were the only ones [IRRI people in Ceylon and almost the only Americans!] and so everybody who was coming through, of course, either stayed with us or we entertained them. That was really fun for me. It was a very, very nice 2 years that we spent there. It wasn’t easy, but it was nice.

Into Africa

After Ceylon, I was disappointed that we didn’t come back to IRRI. I wanted to come back. I wasn’t all that keen on going to Africa. We had arm-twisting sessions in New York with [Richard] Bradfield [IRRI agronomist, 1963-71] and the Rockefeller people who talked us into the job. We knew that it was important. We knew that this new institution [the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA)] needed what Jim could offer, and in the end we decided that we would do it and we went to Nigeria [in 1970]. Jim enjoyed IITA. He first went there as the rice specialist. Together with the resident Nigerian rice breeder, he developed the rice program and then became the farming systems leader. This broadened his scope a lot to include economics and soil and water management. Some of the people whom he hired in the department were just very, very good and very motivated—including Eugene Terry [a future director general of WARDA, the Africa Rice Center, 1987-96]. It was a big department with respected Nigerian staff too. Then, Jim was offered the outreach director position. He accepted and traveled all over Africa putting in programs. I don’t think he ever got to South Africa; he traveled mostly in the middle part of Africa. It was dangerous in many respects, mostly traveling in a small plane. It was very nerveracking for me. Internal travel while we were in Nigeria was really very difficult because the roads were so bad. So, I didn’t get to do very much traveling in Africa myself.

Still alive

Without Frank Byrnes [IRRI’s first communications specialist, 1963-67], I would have lost contact with the international life after Jim died [of a brain tumor at the age of 55 in New York] in 1983. He’s the one that made a real effort to keep me informed of what was going on at IRRI. His friendship continued after I moved to Dallas about 3 years after Jim died. I really didn’t emerge for several more years until Frank invited me to Winrock [International; a nonprofit organization associated with the Rockefeller Foundation, where several former IRRI staff worked] in February 1989. This sort of jolted me out of my grief. It took me such a long time to recover because the boys were my major concern, and my fledging career and our move to Dallas were also major distractions. So, I really hadn’t come out of it until I met Frank at Winrock. Finally, I could say I’m still alive; I’m still here.

Dirty boots and rice widows

Bob and Sunny Chandler were incredible people—inspiring, energetic, devoted, and generous. Bob had very little patience for trivia, however. He wanted everybody—all the scientists—to get their boots dirty right away, be out in the field. In fact, the story was he would go around and look at the boots. If a staff member hadn’t been in the field that day, there were questions. Of course, Jim had no problem with that. Agronomy is the field. We admired both of them greatly and I learned so much from Sunny. Apart from my mother, she had more influence on me as a developing, maturing young woman than anyone else in my life and that holds true today. Yes, we [the spouses of the early IRRI international staff] were rice widows. I think Bob Chandler actually coined that phrase. And that’s what we called ourselves. He was an empathetic man and recognized our plight, but IRRI scientists, often away from home for long periods, had a job to do and we appreciated and supported that.