The world food crisis of 1973-75 continues to shape the attitude of Asian policymakers toward food security. Occurring as it did in a period of volatility in the world rice market, the crisis has encouraged policymakers ever since to pursue self-sufficiency in rice at all costs.

Analysis of the changing structure of the post-World War II market, and in particular of sturdy trends over the past 2 decades, suggests that Asian rice importers can now afford to rely on the world market for assured access to adequate supplies of affordable rice more than was warranted in the past.

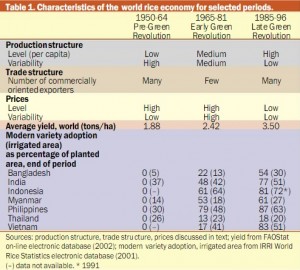

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, Asian rice harvests rose steadily in per capita terms and became more stable. Prices and their variability nevertheless exhibited three distinct phases. Rice prices were high and relatively stable in 1950-64, still high but substantially more variable in 1965-81, and low and very stable in 1985-96 (Table 1).

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, Asian rice harvests rose steadily in per capita terms and became more stable. Prices and their variability nevertheless exhibited three distinct phases. Rice prices were high and relatively stable in 1950-64, still high but substantially more variable in 1965-81, and low and very stable in 1985-96 (Table 1).

Trends in the level and stability of Asian rice production go a long way toward explaining recent trends in world rice prices. Most strikingly, the plunge in world prices in 1982-84 coincided exactly with a sharp increase in per capita rice production in Asia. Since this production surge, the magnitude of year-to-year fluctuations in per capita production has been markedly lower than previously, with fluctuations greater than 3% occurring only 4 times in the past 2 decades, compared to 22 times in the 29 years from 1952 to 1980.

The average absolute value of annual changes in per capita production was 4.4% in 1952-64, 3.7% in 1965-81, and just 1.8% in 1985-96. This improvement in stability is due mainly to the spread of irrigation and improved pest and disease control achieved in part by the development of resistant modern rice varieties.

But why were world rice prices relatively stable in the earlier 1950-64 period despite very unstable production? For most of the 20th century, the major rice exporters were in mainland Southeast Asia: Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia and Vietnam. (The United States is also a major exporter, but its shipments of japonica rice within the Americas are peripheral to the world market, whose prices reflect the Asian trade in indica rice.)

During the 1950s, Myanmar and Thailand dominated world rice exports, with Cambodia also being an important player. More important, exports were a large share of domestic production for these countries encouraging them to be commercially oriented, reliable suppliers.

Thus, whenever a shortfall in Asian rice production occurred, one or more would typically step in to fill the breach and prevent world prices from spiraling out of control.

Constrained exports

The situation had changed considerably by the mid-1960s, when a major El Niño event led to a sharp fall of 6% in per capita Asian rice production in 1965 (see Rice Today, Vol. 2, No. 2, pages 10-19). By this time, Myanmar was well into a period of sharp decline due to restrictive government policies, and the proportion of Cambodia’s production that found its way onto the world market was falling.

South Vietnam banned exports in 1965 and even Thailand was becoming less commercially oriented and more willing to constrain exports to stabilize domestic prices. By the 1970s, the world market was even more unsettled, as production shortfalls caused by severe El Niño and La Niña events were exacerbated by the inaction of the traditional commercial rice exporters — the situation that snowballed into the world food crisis of 1973-75.

The subsequent reemergence of Thailand and Vietnam as commercially-oriented rice exporters was a major factor in buffering the world market in 1998 in the face of a major El Niño event. Other key exporters complement Thailand and Vietnam— notably Pakistan, China and India— and their willingness to supply the world market lends added stability in times of crisis.

The future?

What does the future hold for the world rice market? Prices declined substantially in the last half of the 1990s. The magnitude of this drop recalls the steep decline that occurred in the early to mid-1980s, and the reasons behind it are similar: broadly higher production, curtailed Indonesian imports and a weak Thai baht.

Statistical analysis of these factors and other key trends suggests that prices will remain near their current low levels for the medium term. The one possible countervailing factor is the long-term slowdown in yield growth that has occurred throughout Asia. If yield growth continues to decelerate, and does so more quickly than population growth, per capita production will begin to decline, and this may cause rice prices to rise again.

That said, world prices will likely remain generally stable in the near future, just as they have during the past 15 years, due to the prevalence of irrigation in rice production, the improved pest and disease resistance of modern varieties and — a factor that has received little fanfare — the renewed commercial orientation of major rice exporters. None of these trends is likely to reverse, and Myanmar and Cambodia may rejoin the ranks of stabilizing exporters within the next decade.

That said, world prices will likely remain generally stable in the near future, just as they have during the past 15 years, due to the prevalence of irrigation in rice production, the improved pest and disease resistance of modern varieties and — a factor that has received little fanfare — the renewed commercial orientation of major rice exporters. None of these trends is likely to reverse, and Myanmar and Cambodia may rejoin the ranks of stabilizing exporters within the next decade.

Reduced price variability does not guarantee that the effects of instability are negligible. The effects of even small price fluctuations on the welfare of producers and consumers, especially the poor, can have political repercussions. And, even in a quiet world rice market, financial market liberalization may heighten exchange rate fluctuations that, under free trade, translate into changes in domestic rice prices as readily as do changes in world rice prices. Asian governments need to formulate cost-effective policies to deal with these issues.

Nevertheless, the combination of low and stable prices on the international market will likely continue for the medium term, resulting in less risk for rice-importing countries that decide to rely on the world market more heavily than they have in the past.

_________________________________________

Adapted from Dawe D. 2002. The changing structure of the world rice market, 1950-2000. Food Policy, 27(4):355-370.

_________________________________________

David Dawe is an economist.