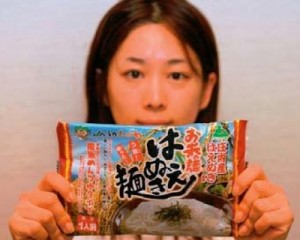

A new rice noodle product, which won a prize in the national food contest held by the agricultural ministry in 2007. (Photo: Masaru Yamada)

Yuko Kimura, a chef at Fukusoen, a traditional noodle restaurant in Tsuruoka City in Yamagata Prefecture, is riding the crest of a wave. After launching the “Haenuki Men” rice noodle in June 2007, Fukusoen, owned by a local agricultural cooperative known as JA, sold 18,000 of the meals by the end of March 2008. Then, from April to June 2008, the restaurant sold almost the same amount again.

Instead of soba, the traditional buckwheat used for noodles, rice flour is the main ingredient of Haenuki Men noodles. By adding some starch from a domestic potato, says Kimura, “We could develop a noodle with a great texture that isn’t available with traditional soba.”

With rice-flour noodles gaining popularity, rice consumption in Japan has increased. The amount of rice destined for noodles is overtaking that used for breads. Rice flour began to be used for breads about 5 years ago as part of a Japanese school lunch program developed to encourage the use of locally produced food, including vegetables and rice. With local government support, more than 8,000 schools—one-third of all lunch-serving schools in Japan—serve rice-fl our breads now.

And the trend is not limited to the public sector, with an increasing number of private companies also interested in rice flour.

Lawson, a company that owns 24-hour convenience stores, announced earlier this year that they would begin to sell rice-fl our breads at around 8,500 shops from September. In Japan, the new demand for products such as those made from rice flour is currently responsible for the consumption of around 6,000 tons of rice per year. It is believed that Lawson’s contribution alone will more than double this figure.

Yamazaki Bakery, a major baking company that also sells rice-flour breads, has expanded its market to the whole of Japan, selling about 50,000 loaves of rice-flour bread per month. According to a Yamazaki representative, “The novelty of using rice flour and the use of local rice appeal to consumers. We plan to offer a range of rice-flour breads.”

Improvements in milling technology are extending the advantages of rice flour. The finer it is milled, the “stickier” rice fl our becomes—a property that gels with consumer tastes. In this light, Starbucks Coffee Japan began offering rice-fl our rolls in June.

“The sticky taste goes with coffee very well,” says a Starbucks spokesperson. “And, because wheat has become much more expensive, the price difference between wheat and rice flour has dwindled.”

This point underlies the fact that Japan, which is self-sufficient in rice but must import much of its wheat, was not directly affected by the rice-price spike in 2008.

Rice flour itself is not new to Japan, which has a history of thousands of years of rice production. However, breads, noodles, cakes, and many other products previously thought to require wheat as a main ingredient are now being made from rice flour—and they are gaining great favor in Japan.

So, what are the reasons? First, skyrocketing international grain prices have made Japanese rice, which is segregated from the international market by high tariffs, more competitive. Second, recent scandals with many imported food items have prompted Japanese consumers to seek more locally grown food, which is seen as safe and tasty.

Another advantage of rice flour is that it isn’t always necessary to add gluten, which can cause allergies. Although products such as bread, which uses rough rice fl our, require gluten, products such as cakes and cookies, which use fi ner rice flour, do not. So, even people who are allergic to flour can eat rice-fl our cakes and cookies without anxiety. Awareness of rice-flour products is growing fast. In 2003, less than 7% of Japanese consumers knew of rice flour bread; in 2006, the number jumped to 44%. Although it is becoming smaller, there remains a huge gap between Japan’s domestic rice prices and international prices. The Japanese government is, however, trying to close that gap. For instance, the government has given away free rice to companies that try to develop new rice-based food.

With Japan only 40% self sufficient in food (on a caloric basis), the Japanese government is encouraging farmers to produce more rice for these new purposes, because eating more domestically grown rice in any form boosts the self-sufficiency ratio.

In the 1960s, Japan’s average per-capita rice consumption was 118 kilograms. Now, the average Japanese citizen eats less than 60 kilograms. This long-term trend causes problems for Japanese agriculture. Around 40% of the country’s rice fi elds are kept fallow to maintain the supply-demand situation. Nearly 10% of farmland in Japan is now abandoned, with lack of labor being one of the main reasons. Even though farmers are eligible for a subsidy if they set aside rice production and produce other crops, some simply give up their land because alternative crops usually require more skilled labor.

Rapidly growing demand for rice flour therefore looms as a golden opportunity to fix some of the problems faced by Japan’s farming communities.

But farmers in Japan have not been so enthusiastic. Selling rice as a traditional staple is much more attractive than selling it for the new demands. Traditional buyers pay substantially more than newcomers do, although farmers are eligible for a subsidy to compensate for this.

To beef up rice production, new measures taken by the government are directly aiding farmers who grow rice for new uses. More aid will be paid to such farmers than to those growing other crops in idle paddy fields. Farmers growing rice for rice flour and livestock feed will receive 500,000 yen (US$4,800) per hectare per year. This is 30% higher than the amount of aid awarded to farmers who grow soybeans and wheat, for example. The government hopes that this will provide sufficient incentive to grow rice for flour.

One of the most important lessons from recent years is the value of innovative thinking. For a long time, the Japanese rice industry did not develop alternative rice flour–based products because it thought rice should be eaten only as a traditional staple. Now, though, it is clear that more consumers want to eat less conventional items. And, the industry is jumping at the chance.