Merle Shepard has been working for 13 years on an unusual “hobby,” as he describes the process. It has been a long time coming, and Shepard is excited to reveal the result.

Shepard’s pride is a new variety of rice named Charleston Gold. It is an improved aromatic offspring of Carolina Gold, the revered grain that brought Charleston untold wealth during the 18th and 19th centuries (see Carolina Gold and Carolina White rice: a genetic odyssey).

A Clemson University entomologist, Dr. Shepard is in a field of Charleston Gold (see photo above).

Although that large and prosperous economy is gone, rice lives on as an essential and celebrated part of Lowcountry (a region in South Carolina) cuisine. Carolina Gold survives as a niche product sold to restaurants, by mail order, and in select grocery stores.

Dr. Shepard is doing his part to preserve the rice’s cultural value. At the same time, he and other scientists are creating an opportunity for more profitable rice farming in the future. Charleston Gold is expected to have the needed blessings for larger-scale commercial growing by March 2012.

It piqued my interest

Dr. Shepard is an emeritus professor of entomology who works at the Clemson Coastal Research and Education Center on U.S. Highway 17 in West Ashley, South Carolina.

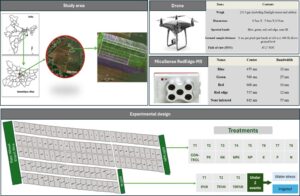

Enamored with Carolina Gold but in search of a better rice, he started a breeding program in 1998 at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines.

He had worked at IRRI for 5 years in the ’80s as its head of entomology, following a dozen years teaching at Clemson. He came back to the Clemson system in 1988. “When I got to Charleston, realizing this was one of the biggest rice-growing areas in the States at one time, it immediately piqued my interest,” Dr. Shepard says.

Dr. Shepard wanted to know whether rice could be developed with the best characteristics of Carolina Gold—long grain, delicious taste, aroma, and its striking golden hulls—combined with the genetic strength of a modern-day rice, one that resists diseases and other plights.

Gurdev Khush, former head of IRRI’s Plant Breeding and Genetics Division and winner of the World Food Prize in 1996, made the first cross. It was between Carolina Gold and IR64, a long-grain rice widely grown in Asia with a shorter stature and “lodging” resistance.

Lodgingis an often fatal condition seen in older, tall-growing rice varieties. It happens during heavy winds and hard rains.

“The plants just lie down, like a big animal lying down in the middle of the field,” says Dr. Shepard.

“Charleston Gold’s grain is longer and more slender than its Carolina Gold parent and it cooks dry and flaky,” Dr. Shepard says. He indicated that lodging, in addition to the loss of slave labor, was another reason for the demise of the Lowcountry’s rice industry. A series of weather events following the Civil War caused the rice to lodge, “so the yields were almost nothing.

“IR64, developed by Dr. Khush, also has some other advantages,” Dr. Shepard adds. “This variety doubles or quadruples the yield of the old Asian varieties. And it tastes pretty darn good.”

Dr. Khush went on to make a second cross at the Institute, and then began the process of selection, successive years of test crops and identifying the strongest plants in each generation.

Looking for Gold

Dr. Shepard received his first packets of rice seed from the Philippines in 2001. He started growing them out the next year and winnowed the original 25 family lines to 12, then 4.

By 2005, “We tentatively saw one that popped out above all the rest. We were already calling it Charleston Gold, although it was not really a named variety.”

Within the next few years, the chosen rice underwent further evaluation by Anna McClung, a rice breeder and researcher in Texas. McClung did the “finishing”—making sure the new breed, true to type, was not producing rogue plants.

Charleston Gold also was grown in different places, in part to determine its hardiness against fungal diseases under different growing conditions. According to Dr. Shepard, it proved to have excellent broad-spectrum disease resistance.

“This is particularly important in organic production because you don’t have to treat these diseases with any chemicals,” he said. “Charleston Gold is perfectly fitted to an organic market.”

Organics are growing about 20% a year, Dr. Shepard points out. “More and more people are going for organic stuff. I think there is a huge place for things like these grains.”

A wonderful rice

Glenn Roberts of Anson Mills in Columbia and president of the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation also sees a bright future for the new rice.

He says Charleston Gold has the right characteristics to become a significant part of the market. Dubbed an “artisanal grain guru,” Mr. Roberts works with organic grain growers in several states. He sells his products worldwide, including to more than 2,000 chefs in the United States.

He has already sold about 40,000 pounds (20,000 kg) of Charleston Gold this year, and says demand is growing every month.

“It’s a wonderful rice,” Mr. Roberts says. “I like the nuances.”

Specifically, he thinks the rice ages well, with changes in flavor and texture that make it even more elegant and floral with time. He also says Charleston Gold is a good reflector of its terroir. “I love the idea that you can taste the ground and the water in the rice.” But, “This does not take away from Carolina Gold,” he points out. “It just increases the rice market and brings more attention to Charleston.”

Brooke Byrd of Carolina Plantation Rice in Darlington, which is also growing Charleston Gold, says Lowcountry consumers can expect to see the new rice in coming months in specialty shops, Whole Foods Market, and in select Piggly Wiggly and Harris Teeter stores. Both Anson Mills and Carolina Plantation Rice are selling it online.

Shepard says he didn’t receive outside funding or grants to specifically pursue the development of Charleston Gold. Dr. Khush and Dr. McClung also joined in purely out of personal interest, he says.

“It was just something we had an intense desire to do and we made it happen.”

_____________________________________________

Ms. Taylor is the food editor ofThe Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina, U.S.A.

——————-

Edited version reprinted with permission from The Post and Courier.