Walter Cronkite, the late great reporter for CBS News in the U.S., once said, “A career can be called a success if one can look back and say, ‘I made a difference.’” By this measure, four new International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) alumni, who retired in 2017, have been extremely successful. It is poignant that Roland Buresh, J.K. Ladha, Noel Magor, and Nollie Vera Cruz all boxed their papers and passed the baton on to their successors last year. But, it is certainly uplifting to revisit their time at IRRI over a combined 119 years of service to the institute. Fortunately, they were able to include me in their busy schedules for respective well-earned Pioneer Interviews before they departed for new adventures in retirement. In Part 1, Roland and J.K. discuss their days at IRRI. Part 2 will feature Noel and Nollie in the April-June issue of Rice Today.

Forty years in the mud

Roland Buresh, who spent 24 years at IRRI as a soil scientist, worked primarily on nutrient and crop management, first as a visiting scientist in a 7-year stint in 1984-91 and then again to stay as a senior scientist in 2000 and as a principal scientist from 2010. Add to this his stints as a soil scientist at the International Centre for Research in Agroforestry (now World Forestry Center) in Nairobi, Kenya, and the International Fertilizer Development Center in the U.S,, and this son of a Minnesota dairy farmer has, as he puts it, had a 40-year journey through the mud.

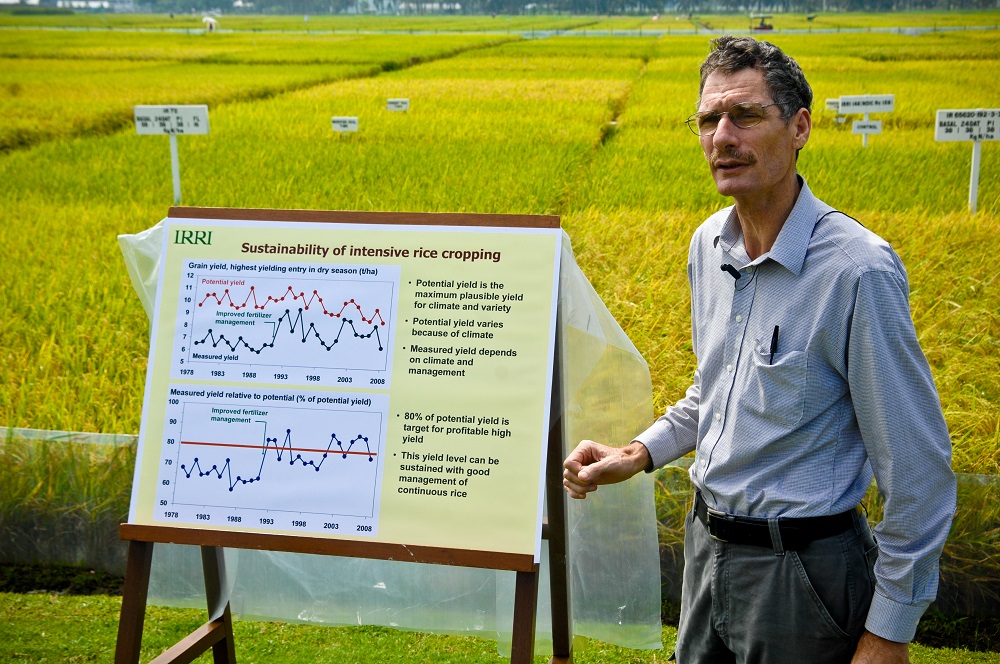

With an MS degree in soil science from North Dakota State University and a PhD in marine sciences from Louisiana State University, Roland, at IRRI, focused on site-specific nutrient management (SSNM) as well as sustainable management of intensive irrigated rice, crop residue, and rice-maize cropping systems. He also guided IRRI’s Long-Term Continuous Cropping Experiment (LTCCE), one of the world’s longest-running agricultural trials. As a spin-off from the SSNM work, Roland pioneered the development of various innovative knowledge transfer tools, culminating with Rice Crop Manager, which specifically aids small-scale farmers in Asia.

“When I came to IRRI in 2000, I inherited the institute’s SSNM research,” he explained. “This concept had been pioneered by agronomist Achim Dobermann and other scientists. In the 1990s, IRRI had already been very successful in developing and publishing the scientific principles for better site-specific management of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilizers.”

The challenge at that stage was to take this excellent science to the farmers. So, one of Roland’s major tasks in the ensuing 17 years was to help take this scientifically proven technology into the hands of farmers.

“Along the way, we tried a number of things,” recalled Roland. “First, we met with farmers to get a better understanding of their problems. That led to refinement of the leaf color chart to help determine nitrogen application rates. Eventually, we produced other printed materials in which SSNM principles were presented to extension workers and farmers. By 2006-07, we had developed one-page quick guides on how to manage fertilizer depending on yield targets and the crop-growing environment. In fact, for the Philippines, we developed quick-guide fertilizer recommendations based on SSNM principles for every rice-growing province in the country.”

And then one morning, during his daily 4-km walk from home to office, it suddenly struck Roland that, if a farmer were asked approximately 10 questions about his or her specific farming situation and goals, an extension agent could use the answers to construct a field-specific fertilizer recommendation that would be unique to that farmer’s field. “That was the breakthrough!” Roland said.

However, even with the answers, it would not be easy for an extension worker to identify the correct recommendation from just the printed materials that IRRI had developed.

“Then, I got the idea in 2008, why not use a computer to make the calculations,” he chimed. “That’s how Nutrient Manager for Rice got started. It was initially programmed in Microsoft Access for the Philippines and then other countries, such as Indonesia and Bangladesh.”

This effort required very close collaboration with national programs to obtain a better understanding of local crop-growing environments and to tailor questions for translating into local languages. “The next step was to try different versions of mobile smartphone applications,” Roland added. “Interactive voice response was quite successful, especially in the Philippines and Indonesia.”

Finally, when integrating this technology into web-based programs, Roland and his team realized that nutrient management recommendations alone were not enough for farmers. “There was a real need for additional information on the rice crop itself, such as variety used, how many crops each year, irrigated or rainfed, type of nursery preparation and transplanting, etc.,” he said. “So, in 2013, we developed Rice Crop Manager, which provides farmers with personalized crop and nutrient management guidelines. We’ve been particularly fortunate in the Philippines to have support from the government through its Department of Agriculture and the National Rice Program. Their funding and assistance have facilitated more research on and key dissemination of this technology.”

Dr. Buresh explains the importance of the LTCCE to Bill Gates. He managed the landmark experiment at IRRI for 17 years. (Photo by Isagani Serrano, IRRI)

In the four years after the introduction of Rice Crop Manager, 1.2 million recommendations have been generated and provided as printed guides to Filipino farmers. Certainly, an innovative way to make a difference for farmers!

Another of Roland’s major projects was the LTCCE, in which more than 150 rice crops (three times annually) have now been grown continuously without a break since 1962. He believes the LTCCE has brought varieties together with good water and fertilizer management to allow researchers to make recommendations to sustain rice production (see A never-ending season).

“The yield trends that we have observed through time in the LTCCE are driven in good part by variations in weather,” he pointed out. “There’s not only a difference between wet and dry seasons but also from year to year. Now, with a long historical record of yields and crop performance across seasons and years to analyze, I believe we have a unique opportunity to really look at sustainability from the perspective of change in climate, which involves dealing with increasing nighttime temperatures and changes in solar radiation.”

In recognition of his innovative work to make a difference for Asian farmers, Roland won the International Fertilizer Association’s 2011 Norman Borlaug Award for excellence in crop nutrition research. He received the 2016 People’s Republic of China Friendship Award for his contributions to nutrient and crop management technology now used on 40% of the rice-growing area in Guangdong Province and steadily expanding elsewhere in China.

Grappling with an enigma and nurturing future scientists

Jagdish Kumar “J.K.” Ladha, another retiring soil scientist with a long service to IRRI, is recognized internationally as an authority on cereal systems research, conservation agriculture, soil fertility, and plant nutrition. Hailing from Gwalior, a major city in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, he was interested, at an early age, in the tiny microbes that exist everywhere in nature, especially in plants and the soil. Armed with a PhD in botany from Banaras Hindu University, he set out in 1976 on a career in agriculture to do research on soil microbiology, fertility and plant nutrition, and cereal systems, subjects on which he has subsequently authored or co-authored more than 200 internationally refereed journal articles and 13 books.

Intrigued by the work at IRRI that had led to the high-yielding semi-dwarf rice varieties, such as IR8, he came to the institute as a postdoctoral fellow in 1980 for a “short” posting that ended 37 years later!

“I stayed all these years because I truly enjoyed the work here and the potential for achievement,” J.K. relayed. “Over this time, I’ve managed several soil microbiology and nutrition research projects and have had some administrative responsibilities, including coordinating the Rice-Wheat Consortium for the Indo-Gangetic Plains and heading the IRRI-India Program for 12 years.”

J.K. believes he has made the biggest difference in nurturing the next generation of rice scientists. “It’s very rewarding when these people finish their degree or nondegree training and then go back home to make their mark, some leading their own rice research programs.” (Photo: Isagani Serrano)

Throughout his career, a topic that has continually attracted his attention and interest is nitrogen, an “intriguing enigma,” as he calls it. About half of all nitrogen fertilizer applications go to the three major cereals—rice, maize, and wheat. “Nitrogen’s good side is that the nutrient is required for crop production,” said J.K. “However, the element’s bad side—here referring to synthetic nitrogen—is that excess amounts not used by plants go either into the groundwater as nitrate or into the atmosphere as nitrogen oxide, which can cause serious human and animal health problems and air pollution.”

The challenge is to optimize nitrogen use while minimizing its negative impacts. “We have been encouraging farmers to efficiently apply nitrogen fertilizer only when the crop requires it,” said J.K. “One of the most exciting projects for me at IRRI was working back in the 1990s on the international initiative to look into the feasibility of developing cereals, such as rice, that could fix biological nitrogen like legumes do.”

According to J.K., before the idea was put back on the drawing board due to a funding shortage, the researchers determined that it would most likely take some complex genetic engineering to accomplish this, but what an achievement it would be.

Along with his IRRI “comrade in soils,” Roland Buresh, J.K. has analyzed with great interest the data coming out of the LTCCE. “In the experiment, we have watched rice yields decline starting in 1968, all the way through to 2015,” J.K. pointed out. “So, growing three rice crops in a year is too intensive to be sustainable in the long term unless the relationships between varieties and agronomy are addressed. We also have to look at the soil’s microbiology and chemistry over time and how these adjust to changes in climate. The volumes of information coming out of the LTCCE are proving to be very useful in developing and validating new rice-growing models for the future.”

J.K. spent most of his last 15 IRRI years in India as the institute’s country representative. “India has been a very strong natural partner of IRRI from the beginning,” he said. “It’s got all the agro-ecosystems that represent Asia as a whole. When I arrived there in 2004, research was shifting to the new frontier of unfavorable environments in eastern India, where much of the country’s food production is and will be coming from.”

In early August 2017, the Government of India and IRRI further bolstered their partnership with the establishment of the IRRI South Asia Regional Center in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, from where IRRI and India will be conducting joint research on breeding, agronomy, and grain quality, not only for India, but for neighboring countries as well.

“I think it’s remarkable to have this kind of an agreement with India,” J.K. beamed. “This fantastic model for a regional research hub will open the door for duplication in other regions of the developing world.”

During his 12-year stint as IRRI’s representative for India, J.K. met with farmers and even Barack Obama when the then U.S. president visited Mumbai in 2010. (Photo: IRRI)

Notwithstanding all the research J.K. has conducted, he believes that he has made the biggest difference in nurturing the next generation of rice scientists. “I have been fortunate to work with many, many young students from all over Asia and the world,” J.K. smiled. “It’s very rewarding when these people finish their degree or nondegree training and then go back home to make their mark, some leading their own rice research programs.” Related to education, J.K. has also found time to be a prolific writer, having one of the highest numbers of publications cited in the entire CGIAR system, with more than 18,000 listings on the citation index.

J.K. has won numerous accolades throughout his career, including the International Service in Crop Science Award from the Crop Science Society of America (CSSA), the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Soil Conservation Society of India, the International Service in Agronomy Award from the American Society of Agronomy (ASA), the International Service in Soil Science Award from the Soil Science Society of America (SSSA), the International Plant Nutrition Science Award from the International Plant Nutrition Institute, and the Agriculture Prize from the Third World Academy of Sciences. He is also a Fellow of the Indian Academy of Agriculture Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, ASA, SSSA, and CSSA.

Roles for IRRI beyond 2020

Roland and J.K. were asked what they saw as IRRI’s biggest challenge as the institute nears its 60th anniversary in 2020.

Roland believes that the research-to-technology link is critical for impact and a key area for innovations from IRRI now and in the future. “The dissemination part of the pathway is more about partnerships with national systems and creative technical inputs from IRRI,” he said.

“I strongly believe that IRRI must stay on track with frontier areas of research,” said J.K. “The institute must also continue its role as an honest broker that links developed-country advanced institutions and the private sector with national programs. I see this as a much more important function now than when IRRI started in the 1960s.”

____________________

Mr. Hettel is a senior consulting editor and content specialist at IRRI.

It’s a nice work for the nutrition aspects and increasing crop production