Innocent-looking rice plants also engage in courtship and marriage.

The rites are simple, devoid of an elegant and expensive entourage.

The bride, the superstar of the occasion, is not in the usual wedding gown. She is simply a dark green rice plant with flowers stripped off its anthers, the male counterpart of the species.

When rice flower buds are still empty of their stored starch, both male and female parts are in the flower, producing self-fertilized seeds. To prevent self-pollination, castration by removing the male parts by tweezers is a requisite. Only at this point will the rice plant be transformed into an instant bride.

Before the cool evening is over, the bride is locked in a plastic bag to protect her from intruders. She is in seclusion, awaiting her “prince charming” during the long, haunting night. At daybreak, as the sun kisses the rice flowers and the morning dew shies away to join the rain clouds, the innocent bride sees hope for rejoicing—a break from her solitary confinement. Overjoyed to meet the groom, she sneaks through the transparent glassine bag, but, to her disappointment, she finds no one.

The sun radiates more of its inexhaustible energy, unmindful of the dark clouds blocking its efforts to force the sleepy groom out of its capsule. After a long extended wait, “here comes the groom;” not the bride, excited, puzzled, and eager to know who her life partner will be. The groom, who comes from an elite group, is as proud as ever to sire a celebrity noted for the family’s capacity to give high grain yield.

The ceremony begins without church bells, but barely introducing the groom as a golden yellow pollen grain, released by the burning sun from its hideaway. With a mute “I do,” the bride receives him with wide-open arms.

The newlyweds are veiled and bound together, and the traditional wedding ring—simply a brightly colored merchandising tag with a piece of silvery string and a leadcoated paper clip—is pulled out. Inscribed on the tag are the common names of the newlyweds. This is their marriage contract, a contract signed by both parties without an expiration date.

The ceremony is finally over—no wedding cake, doves, or bountiful food for the invited guests. The honeymooners do not go to a five-star hotel. They are left in a dark corner of the greenhouse after being covered with glassine bags, locked with a paper clip. But, this union will be the start of something big—generations of rice varieties that are not hindered by boundaries.

______________________________________

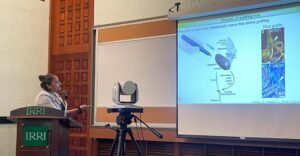

Mr. Herrera was among the first breeders to make crosses at IRRI in the early 1960 (photo above).

He arrived at IRRI in 1961 as a research aide and retired 36 years later in 1997 as a senior assistant scientist.